Entero-colonic Fistula Secondary to Necrotizing Enterocolitis in Premature Infant: A Case Report

Article information

Abstract

Necrotizing enterocolitis is a severe inflammatory disease of the intestine and is the main cause of death in infants, mostly occurring in premature infants. Intestinal obstruction may occur during the medical treatment of necrotizing enterocolitis. A common cause of intestinal obstruction is intestinal stricture, and entero-enteric fistulas may form in the proximal portion of the intestinal stricture. Several mechanisms may be suggested for the development of entero-enteric fistula. Intestinal ischemia and subsequent necrosis do not become intestinal perforation over time, causing an inflammatory reaction, and are attached to the adjacent intestine, forming a fistula. Alternatively, a subacute perforation may be sealed off by the adjacent intestine, resulting in fistula formation. Entero-enteric fistulas are closely related to distal stricture and occurs when there is a localized perforation rather than a generalized perforation. Fistulas can be diagnosed via contrast enema examination or distal loopogram, and surgical resection is required. Here, I report a case of a preterm infant with an entero-colonic fistula secondary to necrotizing enterocolitis. The patient had abdominal distention and bloody stool and was confirmed to have rotavius enteritis. Plain abdominal radiographs showed pneumatosis intestinalis. The patient received medical treatment for necrotizing enterocolitis. While the symptoms were improving, he vomited again, and intestinal obstruction was suspected. Gastrografin enema was performed due to intestinal obstruction, and an enterocolonic fistula was found.

서론

신생아 집중치료 기술이 발전하면서 미숙아 및 저체중 출생아의 생존율이 향상되고 있지만 괴사성 장염의 발병률은 줄어들지 않고 여전히 미숙아 사망의 주된 원인으로 알려져 있다. 괴사성 장염은 신생아 집중치료실에 입원한 환자의 5% [1], 저체중 출생아의 3%–5%에서 발생하며[2], 미숙아뿐만 아니라 만삭아에서도 발생하는데 괴사성 장염 환자 중 6%–13%가 만삭아이다[2]. 괴사성 장염은 내과적 치료에 잘 반응하지만, 환자의 15%–30% 정도에서 내과적 치료 후 수유를 하면서 장 폐색 증상이 생기고 장 폐색 정도에 따라 수술적 치료를 요하는 경우도 있는데 이러한 장 폐색은 허혈성 협착 때문으로 알려져 있다[3]. 장 협착과 달리 괴사성 장염 환자에서 장사이 누공(entero-enteric fistula)은 드물게 발생하여 외국에서 보고된 예는 있으나[4-8], 국내에서 보고된 적은 없다. 저자는 괴사성 장염으로 내과적 치료 중 장 폐색이 생겼던 미숙아에서 장 협착 외에 장사이 누공이 발견되었던 1례를 경험하였기에 보고하는 바이다.

증례

34세 산모가 5일 전부터 생긴 조기 진통으로 타 병원에서 리토드린을 투약 받았지만, 진통이 호전되지 않고 자궁경부 개대가 진행되어 본원으로 전원 후 재태 연령 32주 1일, 출생 체중 1.74 kg의 남아를 질식분만으로 분만하였다. 환자 출생 시 Apgar 점수는 1분 6점, 5분 9점이었고, 태변 착색은 있었지만 흡인은 없었으며, 신생아 집중치료실 입원 후 산소포화도 90% 이상, 활력징후는 체온 36.4 ℃, 맥박 150회/분, 호흡 58회/분으로 특이 소견 없었고, 복부 둘레 24.5 cm이었다. 출생 당일부터 정상적인 태변 배출이 있었으며 생후 3일 이후 이행변이 지속적으로 나왔고, 수유는 분유 5 cc 경관 수유로 시작하여 생후 3일째부터 모유와 함께 혼합 수유하였으며 소화되지 않은 잔량 없이 생후 7일째 수유량 120 cc/kg/day까지 증량하였다. 생후 4일째 시행한 심초음파 검사상 특이 소견은 없었다.

생후 8일째 움직임이 감소하고 끙끙거리며 수유 시 잔량이 있어 금식하였고, 다음날 복부 팽만(복부 둘레 26.5 cm)이 있고 잠혈(occult blood)이 있는 대변을 보았다. 단순 복부 방사선 사진에서 대부분의 장이 팽창되어 있고 창자벽 공기(pneumatosis intestinalis)가 관찰되었다(Figure 1A). 혈액검사에서 혈색소 14.1 g/dL, 총 백혈구 수 19,860/μL, 혈소판 수 237,000/μL, C-반응단백(C-reactive protein, CRP) 0.3 mg/dL이었고, 대변 바이러스 항원 검사에서 Rotavirus 양성이었으며 혈액 및 대변 배양에서 동정된 세균은 없었다. 이에 괴사성 장염 IIB 병기 진단하에[9] 금식, 총 정맥영양, 항생제 정주 치료를 시작하였고, 생후 11일째 혈변이 육안으로 관찰되었고 체온 37.4 ℃, CRP 27.4 mg/dL이었으며 혈액검사에서 혈색소 9.6 g/dL, 총 백혈구 수 3,700/μL, 혈소판 수 7,000/μL이어서 수혈하였다. 2주간의 내과적 치료에도 잠혈 있는 대변, 복부 팽만(복부 둘레 31 cm), CRP 상승 소견 지속되어 1주간 항생제 정주 치료 계속하였다. 생후 36일째 복부 팽만 감소(복부 둘레 27 cm)하고 잠혈 없는 정상 대변 배출되었으며 CRP 0.4 mg/dL로 감소하는 등 환자 상태 호전되어 생후 40일째 분유 경관 수유를 재개하여 생후 45일째 수유량 90 cc/kg/day까지 증량하였다. 하지만 생후 46일째 담즙성 구토를 하였고, 생후 51일째 복부 팽만(복부 둘레 29 cm)과 구토 계속되고 단순 복부 방사선 사진에서 상복부의 소장은 팽창되어 있고 대장은 팽창되어 있지 않는 장 폐색 소견이 보였다(Figure 1B). 생후 52일째 장 폐색 유무를 알기 위해 수용성 조영제(Gastrografin, diatrizoate meglumine, Schering)를 이용한 대장 조영술을 시행하였고, 대장 조영술에서 조영제가 상행결장과 회장 말단부에 차기 전에 공장이 보이고(Figure 2A) 이어 연속된 검사에서 비장 굴곡 근처의 횡행결장과 공장 사이에서 누공이 관찰되었다(Figure 2B). 생후 55일째 수술을 시행하였으며, 수술 소견상 좌상복부의 횡행결장과 공장 사이에 누공이 있었고 근위부 회장에 협착이 있었으며 우하복부에 회장이 유착되어 뭉쳐져 있었다. 이에 누공을 제거하고 누공이 있었던 횡행결장과 공장은 각각 일차 봉합하였고, 회장의 협착 부위를 제거하고 문합술을 시행하였으며, 우하복부의 유착되어 뭉쳐져 있던 회장을 약 10 cm 정도 제거하고 문합술을 시행하였다. 생후 64일째 수술 부위 벌어지며 담즙성 체액 누출이 있었다. 장천공 의심하에 생후 66일째 재수술하였고 회장에 천공이 있어서 일차 봉합술을 시행하고 벌어진 수술 부위는 변연절제술(debridement)을 시행하였다. 생후 73일째 체온 36.8 ℃, CRP 0.5 mg/dL, 총 백혈구 수 9,870/μL로 염증 소견 없고 혈액 및 대변 배양에서 동정된 세균 없어서 항생제 정주 치료 중단하였다. 생후 79일째 경관으로 분유 수유 시작하였고, 수유량 점진적으로 증가되어 생후 85일째 중심정맥도관 제거하였으며, 전신 상태 양호하고 수유량이 103 cc/kg/day에 이르러 생후 110일째 퇴원하였다(Figure 3). 생후 5개월에 외래 방문하였고 특수 분유 수유 중으로 체중은 4.2 kg으로 3.0 백분위 미만에 해당해 추후 성장 발달 과정을 추적 관찰하기로 하였다.

(A) Plain abdominal radiograph taken at hospital day 8, shows multiple dilated bowel loops throughout the abdomen. Linear bands of radiolucency that are parallel to the bowel wall are noted, which indicate pneumatosis intestinalis (arrows). (B) Plain abdominal radiograph taken at hospital day 51, shows dilated small bowels (arrows) in upper abdomen and paucity of colonic gas, suggesting intestinal obstruction.

Gastrografin enema examination taken at hospital day 52. (A) Part of the transverse colon (arrowheads) is opacified with contrast media and the ascending colon is not yet visible, but the small bowel (black arrows) is filled with contrast media. (B) Fistula (white arrow) is noted between the transverse colon and the jejunum. Transverse colon (arrowheads) and ascending colon (asterisk) are collapsed, but the small bowel (black arrows) is dilated. Considering that the small bowel filled with contrast media is dilated, it can be assumed that the obstruction is more distal than visible small bowel.

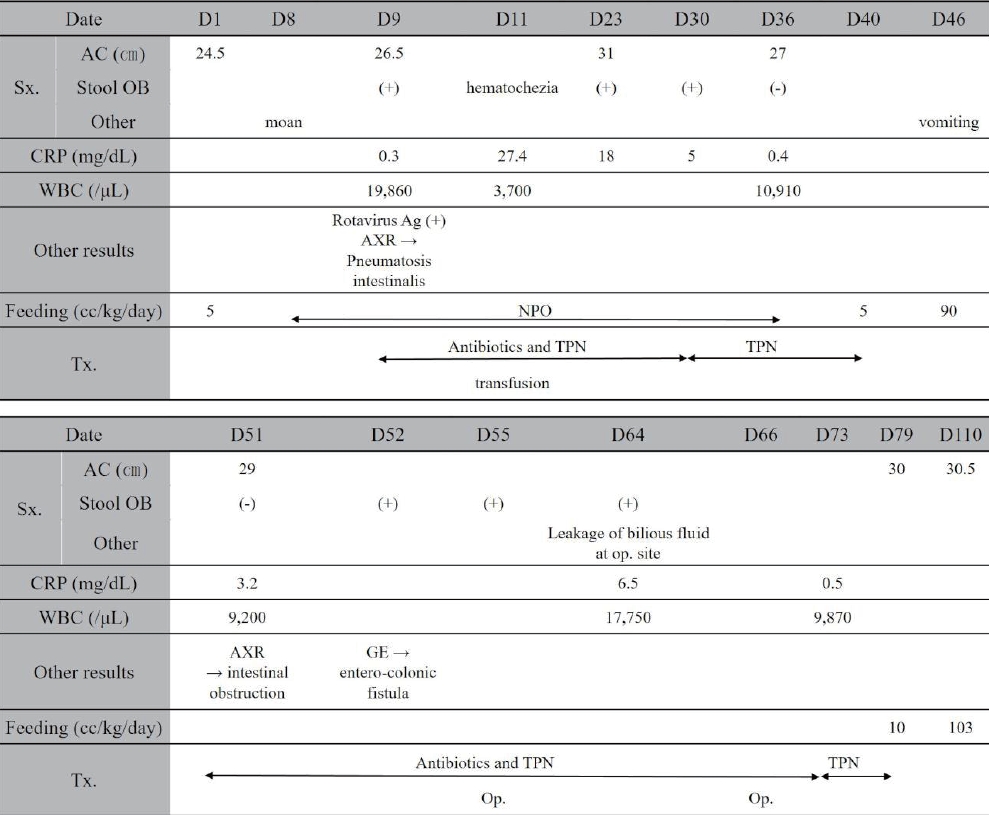

Clinical course of patient. Abbreviations: D, hospital day; Sx., symptom; AC, abdominal circumference; OB, occult blood; CRP, C-reactive protein; WBC, white blood cell count; Ag, antigen; AXR, abdominal X-ray; NPO, nothing per oral; Tx, treatment; TPN, total parenteral nutrition; Op., operation; GE, gastrografin enema.

고찰

괴사성 장염은 장 점막 또는 장벽 전층에 다양한 정도의 괴사가 생기는 염증성 질환으로 정확한 병인은 밝혀지지 않았지만 미숙아의 숙주방어부전(impaired host defense), 장관 영양, 세균 부산물, 장 허혈 등이 장 손상을 일으키는 염증 연쇄반응(inflammatory cascade)을 활성화하는 것으로 알려져 있다[10]. 괴사성 장염은 복부 팽만, 위 잔류량 증가, 혈변, 담즙성 구토와 같은 위장관 증상과 무호흡, 체온 변화, 저혈압 같은 전신 증상이 있을 때 영상 검사와 혈액 검사를 통해 진단한다[11]. 괴사성 장염은 대부분 금식 및 광범위 항생제 정주 같은 내과적 치료로 호전되지만, 장천공에 의한 기복증, 내과적 치료에도 임상 경과의 악화, 장 폐색, 패혈증을 동반한 복부 종괴 등이 있을 때 수술적 치료가 필요하고[3], 괴사성 장염 환자의 약 25% 정도에서 수술적 치료를 받았다는 연구가 있다[12].

장 협착은 괴사성 장염의 잘 알려진 합병증으로[4,6] 장 폐색을 일으키며 발생 빈도는 10%–25% 정도이고 회장과 대장에 잘 생긴다[4]. 하지만 장사이 누공 형성은 드물고[5-8], 대부분 불완전한 장 폐색 및 재발성 패혈증 증상을 보이며 염증 덩어리가 만져질 수도 있다[4]. Stringer 등[4]이 130명의 괴사성 장염 환자를 대상으로 한 연구에서 장사이 누공을 가진 환자는 5명(4%)에 불과하였는데, 5명 모두 괴사성 장염 II 또는 III 병기였고 단순 복부 방사선 사진에서 창자벽 공기가 관찰되었다. 누공의 발생 부위는 2명은 공장과 대장 사이, 2명은 회장과 대장 사이, 1명은 대장과 대장 사이였다. 다른 보고들에서도 장사이 누공은 대부분 괴사성 장염 II 또는 III 병기 환자에서 생겼지만[5,6] 기복증이나 창자벽 공기 소견 없는 괴사성 장염 I 병기에서 생긴 증례 보고도 있다[7].

괴사성 장염 환자에서 누공이 형성되는 기전은 정확히 밝혀지지 않았지만, Levin 등[8]은 장 허혈과 그에 따른 장 괴사가 장 천공으로 되지 않고 염증 반응을 일으켜 염증이 있는 장이 인접한 장에 부착 되어 누공이 발생하거나, 아급성 천공이 인접한 장에 의해 둘러싸이고 막혀서 누공이 형성될 수 있다고 설명하고 있다. 이와 같은 기전으로 광범위한 장 천공으로 기복증이 생겼을 때보다 국소적으로 장 천공이 있을 때 누공이 잘 생길 수 있다는 보고가 있다[4,7]. 괴사성 장염 환자에서 누공 형성과 관련된 가장 중요한 인자로 원위부 협착이 있는데 대부분의 보고에서 누공의 원위부에 협착이 동반되었다[4,7,8]. Stringer 등[4]은 기존의 원위부 협착 없이 누공이 생긴 보고들은 영상 검사를 하지 않았거나 염증성 종괴(inflammatory mass)가 협착 부위를 가려서 협착이 보이지 않았을 것이라고 추정하였다.

장사이 누공은 단순 복부 사진이나 초음파 검사로 진단할 수 없 기 때문에 수용성 조영제를 이용한 대장 조영술 또는 원위 루포그램(loopogram)이 진단에 유용한 검사이고, 소장 사이에서 누공이 생겼을 때는 소장 조영술에서 진단될 수 있다[4]. 괴사성 장염 환자에서 생긴 장 협착은 수술적 치료 없이 호전되는 경우가 있어서 증상이 없을 경우에는 수술하지 않지만, 장사이 누공은 수술적 치료가 필요하다[6]. 수술 시기는 환자의 상태와 지속적인 패혈증 및 영양과 같은 요인에 의해 결정해야 하고, 누공 절제수술은 효과적이지만 경우에 따라서는 짧은창자증후군(short bowel syndrome)이 생길 수 있다[4].

장사이 누공은 드물지만 괴사성 장염 환자에서 생길 수 있는 합병증으로 장 폐색 증상이 있어 대장 조영술을 하는 과정에서 발견하게 되어 문헌 고찰과 함께 보고하는 바이다.

Notes

Ethical statement

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of Sanggye Paik Hospital, Inje University College of Medicine (IRB No. SGPAIK 2023-07-006). Written informed consent by the patient was waived due to a retrospective nature of our study.

Conflicts of interest

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

Author contributions

Conception or design: S.H.K.

Acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data: S.H.K.

Drafting the work or revising: S.H.K.

Final approval of the manuscript: S.H.K.

Funding

None

Acknowledgements

None