|

|

- Search

| Neonatal Med > Volume 28(1); 2021 > Article |

|

Abstract

Purpose

Premature infants have immature respiratory control and cerebral autoregulation. We aimed to investigate changes in cerebral oxygenation during apnea with and without peripheral oxygen desaturation in premature infants.

Methods

This prospective observational study was conducted at Inha University Hospital. Near-infrared spectroscopy (NIRS)-monitored regional cerebral oxygen saturation (rScO2) and pulse oximeter-monitored peripheral oxygen saturation (SpO2) were assessed during the first week of life in 16 stable, spontaneously breathing preterm infants. Apneic episodes that lasted for ≥20 seconds or were accompanied by desaturation or bradycardia were included for analysis. The average rScO2 value during the 5-minute prior to apnea (baseline), the lowest rScO2 value following apnea (nadir), the time to recover to baseline (recovery time), the area under the curve (AUC), and the overshoot above the baseline after recovery were analyzed.

Results

The median gestational age and birth weight of the infants were 29.2 weeks (interquartile range [IQR], 28.5 to 30.5) and 1,130 g (IQR, 985 to 1,245), respectively. A total of 73 apneic episodes were recorded at a median postnatal age of 2 days (IQR, 1 to 4). The rScO2 decreased significantly following apneic episodes regardless accompanied desaturation. There were no differences in baseline, nadir, or overshoot rScO2 between the two groups. However, the rScO2 AUC for apnea with desaturation was significantly higher than that for apnea without desaturation.

Most preterm infants born before 32 weeks of gestation experience apnea. Despite the frequency of apnea of prematurity, it is not well understood whether apnea in preterm infants is related to cerebral ischemia [1]. Evidence suggests that the total number of days with apnea and the continuation of episodes beyond 36 weeks of postmenstrual age are associated with poor neurodevelopmental outcomes in preterm infants [2-4]. The healthy mature brain has a protective mechanism by which cerebral perfusion is kept constant [5]. This is known as cerebrovascular autoregulation. There is an ongoing debate about whether cerebrovascular autoregulation is present in preterm infants at birth or whether it slowly develops postnatally [6]. However, there is strong evidence that cerebral ischemia due to hypoxia or fluctuations in cerebral perfusion may play a major role in brain injury in preterm infants [7-9].

Since its introduction in 1977 [10], near-infrared spectroscopy (NIRS) has drawn extensive interest as a potential tool for monitoring newborn hemodynamics. It is a portable, safe, and noninvasive technology with high temporal resolution that can provide continuous monitoring of tissue oxygenation to detect hypoxia or ischemia in real time [11,12]. Several studies have reported the high sensitivity of NIRS for detecting changes in cerebral oxygenation during hypoxemic and ischemic events in preterm infants [13-17]. Studies examining the effects of apnea on cerebral oxygenation in preterm infants have shown that even short apneic episodes are associated with reduced cerebral oxygenation, as measured using NIRS [18-20].

A peripheral oxygen saturation (SpO2) of <85%, measured using pulse oximetry, has been identified as significantly impacting cerebral oxygenation in neonates with apnea of prematurity [21]. In preterm infants, an SpO2 of <85% has been shown to correspond to a low partial pressure of oxygen (PaO2) (<40 mm Hg) [22,23]. We aimed to investigate changes in regional cerebral oxygen saturation (rScO2), as monitored by NIRS, during apnea with and without peripheral oxygen desaturation (SpO2 <85%).

This was a prospective observational study conducted in the neonatal intensive care unit of Inha University Hospital, Incheon, Korea. Sixteen stable, spontaneously breathing preterm infants with gestational ages (GA) of <32 weeks were included. Caffeine was administered (loading dose 10 to 20 mg/kg, maintenance dose 5 mg/kg daily) to all infants. Mild respiratory support with nasal continuous positive airway pressure or high-flow nasal cannula therapy was permitted. Infants requiring invasive mechanical ventilation, those with grade 2 or higher intraventricular hemorrhage (IVH), or those with major congenital anomalies were excluded. The Inha University Hospital Institutional Review Board approved the study protocol (2017-03-014), and written informed consent was obtained from the infants’ parents.

Heart rate (HR), SpO2, and rScO2 measurements were started within 24 hours after birth and continued for the first week of life. Apnea was defined as a period with no breathing, (1) lasting for ≥20 seconds, or (2) accompanied by desaturation (SpO2 <85%) or bradycardia (HR <100/min), even if at of shorter duration. Of a total of 135 apneic episodes of 16 patients, we selected 73 episodes that did not overlap within 30 minutes. Because we aimed to investigate the effect on cerebral oxygenation of an individual apneic episode and its difference based on the presence of peripheral desaturation, we excluded repeated or overlapped apneas within 30 minutes. We divided the apneic episodes into two groups: with or without peripheral oxygen desaturation (SpO2 <85%).

Obstetric and neonatal data were collected from medical records. We measured rScO2 using the INVOS 5100 cerebral oximeter (Somanetics Corp., Troy, MI, USA). An INVOS 5100 neonatal sensor was attached to the skin of each infant’s forehead. Continuous measurements with a sampling interval of 5 seconds were recorded and transferred to a personal computer. SpO2 and HR were measured using a Radical-7 Pulse CO-Oximeter (Masimo Corp., Irvine, CA, USA). An LNCS Neo-L adhesive sensor (Masimo Corp.) was attached to the right hand of each infant. Measurements were recorded every 10 seconds and transferred to a personal computer through an RS-232 serial communication port. Data were collected simultaneously using dedicated software. In addition, available data regarding the patients’ clinical characteristics, hemoglobin, hematocrit, and capillary blood gas analysis results were collected.

For each apneic episode, the baseline rScO2 value was calculated as the average during the 5 minutes before the apneic episode. The nadir was recorded as the lowest rScO2 value during the 5 minutes after the onset of apnea. The time to recover to baseline (recovery time), area under the curve (AUC) from baseline, and overshoot following the recovery of rScO2 were also analyzed (Figure 1). Data are summarized as the median and interquartile range (IQR). For statistical analyses, SPSS version 25.0 (SPSS, IBM, Armonk, NY, USA) was used. Data were tested for normal distribution. Repeated-measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to identify within-group and between-group changes in rScO2 over time. Differences in parameters between episodes with and without desaturation were evaluated using the Mann-Whitney U-test and Fisher’s exact test. A P-value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Baseline demographic characteristics of the included patients are presented in Table 1. The median GA and birth weight of the included infants were 29.2 weeks (IQR, 28.5 to 30.5) and 1,130 g (IQR, 985 to 1,245), respectively. All subjects were stable preterm infants who breathed spontaneously and received caffeine to treat apnea of prematurity. One infant had germinal matrix hemorrhage, but none were diagnosed with grade 2 or higher IVH.

A total of 73 episodes of apnea were analyzed. The median postmenstrual and postnatal ages at episodes were 29.6 weeks (IQR, 27.3 to 30.6) and 2 days (IQR, 1 to 4), respectively. Table 2 shows the clinical characteristics of patients at the time of apneic episodes categorized as either with or without desaturation (SpO2 <85%). There were no differences in hemodynamic parameters, respiratory support, blood gas status, position, or comorbidities between the two groups. However, non-feeding status was significantly more common in apneic episodes with desaturation than in those without desaturation (34.5% vs. 4.5%, P=0.002). Reasons for non-feeding during episodes with desaturation were gastric residue (five cases, 17.2%), bowel distension (three cases, 10.3%), and suspicion of necrotizing enterocolitis (two cases, 6.9%); during episodes without desaturation, reasons were gastric residue (one case, 2.3%) and bowel distension (one case, 2.3%).

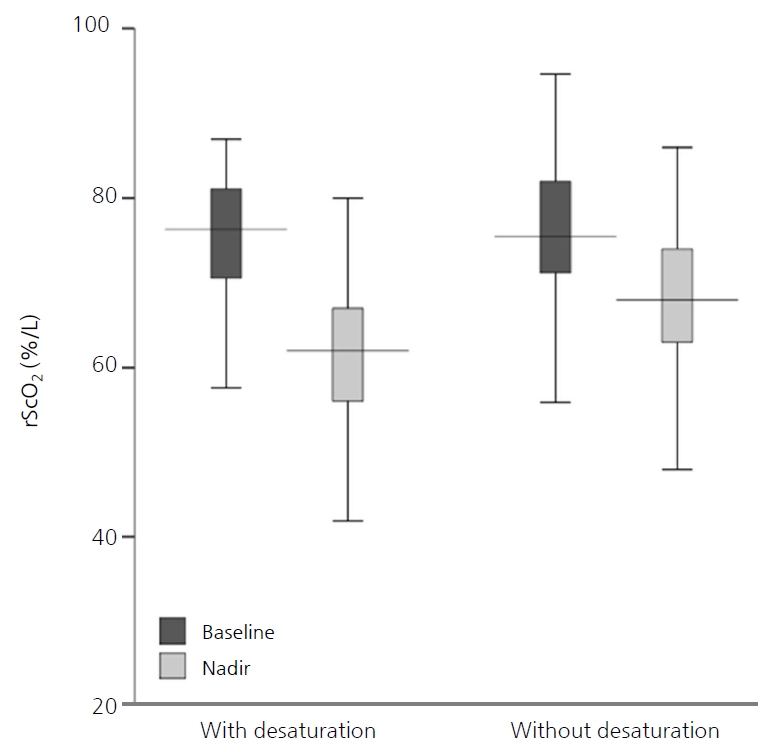

According to the repeated-measures ANOVA, although rScO2 decreased significantly following apnea in both groups (F=382.4, P<0.001), there was no difference between the two groups (F=2.71, P=0.104) (Table 3, Figure 2). The median baseline and nadir rScO2 were not different between the two groups (76.3% [IQR, 70.6 to 81.1] vs. 75.5% [IQR, 71.2 to 82.0], P=0.550; and 62.0% [IQR, 56.0 to 69.5] vs. 68.0% [IQR, 63.0 to 74.0], P=0.053, respectively). However, the median recovery time and AUC of rScO2 were significantly higher in apneic episodes with desaturation than in those without (3.1 minutes [IQR, 1.5 to 4.2] vs. 1.8 minutes [IQR, 1.1 to 3.4], P=0.036; and 15.7 %minutes [IQR, 6.6 to 30.2] vs. 6.2 %minutes [IQR, 3.1 to 14.1], P=0.005, respectively). At the overshoot point, there was an increase in the median rScO2 (1.4 [IQR, 0.6 to 2.5]) for a median of 9.5 seconds (IQR, 5.0 to 20.0) duration after recovery, and this was not different between the two groups (P=0.941). After adjusting for feeding types, only the rScO2 AUC of apnea with desaturation was significantly higher than that of apnea without desaturation (Table 3).

This study shows that, regardless of whether SpO2 is reduced, apneic episodes are associated with a decrease in cerebral oxygenation in very preterm infants. This observation provides important insight into the potentially deleterious effects of repeated episodes of apnea, especially with regard to the possibility of causing or exacerbating hypoxic-ischemic brain injury. When apneic episodes are accompanied by peripheral desaturation, cerebral ischemia could be prolonged, and it could take more time to recover. Additionally, these results contribute to the body of knowledge about the clinical utility of NIRS in monitoring cerebral circulation.

The strong dependence of rScO2 on SpO2 seen in our study is not surprising. NIRS measures the ratio of oxygenated hemoglobin to total hemoglobin in the area covered by a dedicated sensor, which includes a mixture of oxygen saturation values from arterial, capillary, and venous blood [10]. Manufacturers calibrate their devices using the relative weight of the arterial component: 30% for the INVOS 5100 (Somanetics Corp.). Thus, rScO2 is influenced directly by SpO2; however, it is also influenced by cerebral perfusion. Cerebral perfusion is determined by cardiac stroke volume, HR, extracardiac shunts, cerebral perfusion pressure and therefore arterial blood pressure, intracranial pressure, central venous pressure, hemoglobin concentration, blood glucose, arterial carbon dioxide tension and pH value, cerebral regional perfusion, and cerebral oxygen consumption [16,17]. There have been contradictory reports regarding the association of cerebral perfusion with apnea. Perlman and Volpe [1] found a reduction in cerebral blood flow velocity during episodes of apnea, measured using Doppler, especially when accompanied by severe bradycardia (HR <80/min). Livera et al. [24] demonstrated an increase in cerebral blood volume during phases of moderate desaturation and a reduction in cerebral blood volume when apnea was accompanied by bradycardia. However, Payer et al. [20] demonstrated no differences between cerebral blood volume changes in apnea with and without hypoxia. We did not aim to investigate differences in cerebral perfusion according to changes in HR, and there was no difference in the incidence of bradycardia between the two groups (Table 2). However, because cardiac output is known to depend on HR in neonates [20], an episode of significant apnea accompanied by severe or prolonged bradycardia would be expected to cause a decrease in cerebral perfusion, regardless of the presence of hypoxia.

Regarding the association between rScO2 and SpO2, Schmid et al. [25] studied the effects of hypoxemic episodes on cerebral oxygenation in 16 premature infants with lower or higher oxygen target ranges. They found that a lower SpO2 target range was associated with a greater cumulative cerebral desaturation score (representing the area below the baseline value), which could be caused by more frequent SpO2 desaturation events [25]. However, Hunter et al. [15] did not find any correlation between NIRS values and arterial oxygenation in clinically stable preterm infants (between 24 and 31 weeks of gestation; mean, 27.6 weeks). Similarly, we found no differences between baseline rScO2 values in stable preterm infants with apneic episodes with and without arterial desaturation. Moreover, other studies have demonstrated that NIRS readings correlate well with SpO2 in individual preterm infants [26-28], thereby raising the possibility of its use as a trend monitor in the care of preterm patients.

Interestingly, in most of the apneic episodes (62/73, 84.9%) in our study, cerebral saturation briefly increased from baseline for 5 to 20 seconds after recovery from a reduction following apnea, even though none was supported by an increased fraction of inhaled oxygen (FiO2) to assist recovery from apnea. In our study, 17 apneic episodes (23.3%) recovered spontaneously, and tactile stimulation was applied in the remaining cases (76.7%) to facilitate recovery from apnea. However, there were no differences in the levels and durations of rScO2 overshoot between apneic episodes in patients with and without desaturation. Baerts et al. [29] demonstrated a similar post-recovery rScO2 increase, which was significantly higher when FiO2 was additionally increased during the apneic episodes. Our results could be interpreted as follows: cerebral hypoxemia following apnea would result in cerebral hypercapnia and, since partial pressure of carbon dioxide (pCO2) is an important modulator of cerebral perfusion, rather than pO2 [5,30], an increased pCO2 could lead to an increase in cerebral blood flow and compensatory cerebral hyperoxemia. This rebound cerebral hyperoxemia after hypoxemia could result in ischemia-reperfusion cerebral injuries, especially when repeated or prolonged. However, from our data, we could not conclude that more severe cerebral desaturations, as defined by the AUC, were associated with more significant rScO2 overshoots. We speculate that, because our subjects were relatively stable infants, compensatory cerebral hyperoxemia may have been moderate and capable of returning to baseline rapidly, regardless of peripheral systemic desaturation. However, the effects of apnea on rScO2 may be more pronounced and harmful in sick, ventilated, very preterm infants with limited autoregulation of brain circulation. Hence, more studies are needed to clarify this issue.

There are several potential limitations to this study. First, there was an intentional selection bias, in that we excluded repeated episodes of apnea within a 30-minute interval, because we aimed to demonstrate the effects on cerebral oxygenation of individual apneic episodes with and without peripheral desaturation. This selection bias could result in no differences in HR or the frequency of bradycardia between the two groups. Repeated apnea within a short interval likely to be associated with profound desaturation and bradycardia, and would therefore have a more dramatic effect on cerebral oxygenation. Further studies are required to investigate the increased harm to the brain caused by frequently repeated apneic episodes. Second, we did not analyze cerebral fractional tissue oxygen extraction (cFTOE), which reflects regional oxygen delivery or consumption; rather, we analyzed only changes in rScO2 during apneic episodes, whether accompanied by a reduction in SpO2 or not. The cFTOE is calculated as the ratio between peripheral saturation minus cerebral saturation and peripheral saturation [(SpO2–rScO2)/SpO2] [17,31,32]. The actual value monitored by the device was not cFTOE but rScO2. No one has calculated cFTOE when caregivers are watching the rScO2 values and its changes. An additional concern is the fact that changes in cerebral perfusion could result in changes in the rScO2 value, independent of changes in circulating oxygenation. We did not directly measure cerebral blood flow; instead, we selected only stable preterm infants and excluded infants with IVH. There were no differences in factors that could be associated with cerebral perfusion, such as HR, extracardiac shunt (patent ductus arteriosus), blood pressure, hemoglobin concentration, blood glucose, blood pH, or pCO2 [16].

In this study, we observed that cerebral oxygenation in preterm infants can significantly decrease during apnea, especially when accompanied by reduced SpO2 (<85%). Because the NIRS technique does not allow separate measurement of changes in oxygenation and perfusion, it is difficult to comment on whether the brain parenchyma was exposed to hypoxia or not. Since we observed posthypoxic overshoots in cerebral oxygenation, reflecting posthypoxic vasodilation and reperfusion, we can speculate that the brain parenchyma may have been subjected to hypoxia during apnea. This indicates that cerebral desaturation may be an effective indicator of cerebral circulation during apnea in preterm infants. In this context, neuroprotective management could be guided by continuous rScO2 monitoring with regard to systemic-cerebral hemodynamic interactions.

Less is known about the long-term effects of short but frequent episodes of hypoxemia and post-hyperoxemia on the brains of preterm infants. Regardless of the exact mechanism, we can infer that this is likely a contributing factor to neuronal injury and the start of the cascade leading to neuronal death or gliosis. Further studies are warranted to determine the detailed mechanisms and factors influencing rScO2 variation, the rScO2 threshold that indicates brain injuries, and the long-term outcome.

ARTICLE INFORMATION

Figure 1.

Representative tracing of regional cerebral oxygen saturation (rScO2) during an apneic episode, demonstrating the values, time frames, and points of interest used for the analysis during apneic episodes. Baseline: average rScO2 during the 5 minutes before the apneic episode; nadir: the lowest value of rScO2 during the 5 minutes after the onset of apnea; recovery time: time to recover to baseline rScO2; area under the curve (AUC): area of the difference from baseline during recovery; overshoot: the highest value of rScO2 after recovery of rScO2.

Figure 2.

Box plots of cerebral oxygen saturation (rScO2) during apnea with and without peripheral desaturation. According to the repeated-measures analysis of variance, although rScO2 decreased significantly following apnea in both groups (F=382.4, P<0.001), there was no difference between the two groups (F=2.71, P=0.104).

Table 1.

Baseline Demographics of Patients (n=16)

Table 2.

Clinical Characteristics at the Time of Apneic Episodes

Table 3.

Baseline (5-Minute Average), Nadir (during Following 5 Minutes), Recovery Time, and AUC of rScO2

| Variable | Total apnea (n=73) | With desaturation (n=29) | Without desaturation (n=44) | P-value | Adjusted P-value* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| rScO2, baseline | 75.7 (70.8–81.1) | 76.3 (70.6–81.1) | 75.5 (71.2–82.0) | 0.550† | |

| rScO2, nadir | 65.0 (59.0–72.0) | 62.0 (56.0–69.5) | 68.0 (63.0–74.0) | 0.053† | |

| ∆rScO2, decrease at nadir‡ | 10.1 (6.3–15.5) | 12.1 (8.6–20.7) | 8.4 (5.4–11.1) | 0.104† | |

| rScO2 recovery time (min) | 2.0 (1.2–4.0) | 3.1 (1.5–4.2) | 1.8 (1.1–3.4) | 0.036§ | 0.155 |

| rScO2, AUC (% min) | 9.2 (3.9–18.4) | 15.7 (6.6–30.2) | 6.2 (3.1–14.1) | 0.005§ | 0.023 |

| rScO2, overshoot | 76.0 (73.0–83.8) | 76.5 (73.0–84.0) | 76.0 (73.0–83.0) | 0.931† | |

| ∆rScO2, increase at overshoot∥ | 1.4 (0.6–2.5) | 1.4 (0.6–2.3) | 1.4 (0.6–2.8) | 0.941† | |

| Duration of overshoot (sec) | 9.5 (5.0–20.0) | 12.0 (5.0–21.0) | 9.0 (5.0–20.0) | 0.994§ | |

REFERENCES

1. Perlman JM, Volpe JJ. Episodes of apnea and bradycardia in the preterm newborn: impact on cerebral circulation. Pediatrics 1985;76:333–8.

2. Horne RS, Fung AC, NcNeil S, Fyfe KL, Odoi A, Wong FY. The longitudinal effects of persistent apnea on cerebral oxygenation in infants born preterm. J Pediatr 2017;182:79–84.

3. Pillekamp F, Hermann C, Keller T, von Gontard A, Kribs A, Roth B. Factors influencing apnea and bradycardia of prematurity: implications for neurodevelopment. Neonatology 2007;91:155–61.

4. Janvier A, Khairy M, Kokkotis A, Cormier C, Messmer D, Barrington KJ. Apnea is associated with neurodevelopmental impairment in very low birth weight infants. J Perinatol 2004;24:763–8.

6. Kooi EM, Verhagen EA, Elting JW, Czosnyka M, Austin T, Wong FY, et al. Measuring cerebrovascular autoregulation in preterm infants using near-infrared spectroscopy: an overview of the literature. Expert Rev Neurother 2017;17:801–18.

7. Soul JS, Hammer PE, Tsuji M, Saul JP, Bassan H, Limperopoulos C, et al. Fluctuating pressure-passivity is common in the cerebral circulation of sick premature infants. Pediatr Res 2007;61:467–73.

8. Boylan GB, Young K, Panerai RB, Rennie JM, Evans DH. Dynamic cerebral autoregulation in sick newborn infants. Pediatr Res 2000;48:12–7.

9. Moore T, Hennessy EM, Myles J, Johnson SJ, Draper ES, Costeloe KL, et al. Neurological and developmental outcome in extremely preterm children born in England in 1995 and 2006: the EPICure studies. BMJ 2012;345:e7961.

10. Jobsis FF. Noninvasive, infrared monitoring of cerebral and myocardial oxygen sufficiency and circulatory parameters. Science 1977;198:1264–7.

11. Kreeger RN, Ramamoorthy C, Nicolson SC, Ames WA, Hirsch R, Peng LF, et al. Evaluation of pediatric near-infrared cerebral oximeter for cardiac disease. Ann Thorac Surg 2012;94:1527–33.

12. Boas DA, Elwell CE, Ferrari M, Taga G. Twenty years of functional near-infrared spectroscopy: introduction for the special issue. Neuroimage 2014;85 Pt 1:1–5.

13. Da Costa CS, Greisen G, Austin T. Is near-infrared spectroscopy clinically useful in the preterm infant? Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed 2015;100:F558–61.

14. Vesoulis ZA, Liao SM, Mathur AM. Gestational age-dependent relationship between cerebral oxygen extraction and blood pressure. Pediatr Res 2017;82:934–9.

15. Hunter CL, Oei JL, Lui K, Schindler T. Cerebral oxygenation as measured by near-infrared spectroscopy in neonatal intensive care: correlation with arterial oxygenation. Acta Paediatr 2017;106:1073–8.

16. Mayer B, Pohl M, Hummler HD, Schmid MB. Cerebral oxygenation and desaturations in preterm infants: a longitudinal data analysis. J Neonatal Perinatal Med 2017;10:267–73.

17. Wardle SP, Yoxall CW, Weindling AM. Determinants of cerebral fractional oxygen extraction using near infrared spectroscopy in preterm neonates. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 2000;20:272–9.

18. Schmid MB, Hopfner RJ, Lenhof S, Hummler HD, Fuchs H. Cerebral oxygenation during intermittent hypoxemia and bradycardia in preterm infants. Neonatology 2015;107:137–46.

19. Petrova A, Mehta R. Near-infrared spectroscopy in the detection of regional tissue oxygenation during hypoxic events in preterm infants undergoing critical care. Pediatr Crit Care Med 2006;7:449–54.

20. Payer C, Urlesberger B, Pauger M, Muller W. Apnea associated with hypoxia in preterm infants: impact on cerebral blood volume. Brain Dev 2003;25:25–31.

21. Yamamoto A, Yokoyama N, Yonetani M, Uetani Y, Nakamura H, Nakao H. Evaluation of change of cerebral circulation by SpO2 in preterm infants with apneic episodes using near infrared spectroscopy. Pediatr Int 2003;45:661–4.

22. Quine D, Stenson BJ. Arterial oxygen tension (Pao2) values in infants <29 weeks of gestation at currently targeted saturations. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed 2009;94:F51–3.

23. Hay WW Jr, Brockway JM, Eyzaguirre M. Neonatal pulse oximetry: accuracy and reliability. Pediatrics 1989;83:717–22.

24. Livera LN, Spencer SA, Thorniley MS, Wickramasinghe YA, Rolfe P. Effects of hypoxaemia and bradycardia on neonatal cerebral haemodynamics. Arch Dis Child 1991;66(4 Spec No):376–80.

25. Schmid MB, Hopfner RJ, Lenhof S, Hummler HD, Fuchs H. Cerebral desaturations in preterm infants: a crossover trial on influence of oxygen saturation target range. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed 2013;98:F392–8.

26. Wolf M, von Siebenthal K, Keel M, Dietz V, Baenziger O, Bucher HU. Tissue oxygen saturation measured by near infrared spectrophotometry correlates with arterial oxygen saturation during induced oxygenation changes in neonates. Physiol Meas 2000;21:481–91.

27. Fuchs H, Lindner W, Buschko A, Almazam M, Hummler HD, Schmid MB. Brain oxygenation monitoring during neonatal resuscitation of very low birth weight infants. J Perinatol 2012;32:356–62.

28. Brazy JE, Lewis DV, Mitnick MH, Jobsis vander Vliet FF. Noninvasive monitoring of cerebral oxygenation in preterm infants: preliminary observations. Pediatrics 1985;75:217–25.

29. Baerts W, Lemmers PM, van Bel F. Cerebral oxygenation and oxygen extraction in the preterm infant during desaturation: effects of increasing FiO(2) to assist recovery. Neonatology 2011;99:65–72.

30. Kaiser JR, Gauss CH, Williams DK. The effects of hypercapnia on cerebral autoregulation in ventilated very low birth weight infants. Pediatr Res 2005;58:931–5.

-

METRICS

-

- 3 Crossref

- 4,100 View

- 120 Download