The Use of Probiotics in Preterm Infants

Article information

Abstract

Probiotics are live microorganisms that positively affect host health by altering the composition of the host microbiota. Gastrointestinal dysbiosis refers to adverse alterations of the intestinal flora and is associated with several diseases, including necrotizing enterocolitis, late-onset sepsis in preterm infants as well as atopic disease, colic, diabetes, and diarrhea in term infants. The risk factors for gastrointestinal dysbiosis are preterm birth, cesarean section delivery, and formula feeding, in contrast to term birth infants, vaginal delivery and breast milk feeding. Probiotics have been used to restore synbiosis in infants with gastrointestinal dysbiosis. Probiotics inhibit colonization of pathogenic bacteria in the gastrointestinal tract, thereby improving the barrier function of the gastrointestinal tract, and the immune function. In preterm infants, probiotics reduce mortality as well as rates of necrotizing enterocolitis and late-onset sepsis. The combined use of probiotics such as Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium and the combination of probiotics with prebiotics yield better outcomes in the prevention of necrotizing enterocolitis than those achieved with a single pro- or prebiotic strain. However, the routine use of probiotics has been hindered by the lack of pharmaceutical-quality products, and a definite effect has yet to be demonstrated in preterm infants with a birth weight <1,000 g. Therefore, to reduce the risk of necrotizing enterocolitis in preterm infants, probiotics should be provided along with breast milk and other strategies aimed at preventing gastrointestinal dysbiosis.

서론

인체는 이를 구성하는 세포 이외에 피부나 장관 등 여러 곳에 미생물(microorganism)이 집락화되어 있는데, 세균, 진균, 기생충, 바이러스 등 미생물 자체를 미생물균총(microbiota)이라고 하며 이들의 유전물질들을 모두 일컬어 microbiome이라고 한다[1,2]. 미생물균총들이 균형을 이루고 있는 상태를 공생(synbiosis)이라고 하고, 그와 다르게 세균 불균형(dysbiosis)은 어떤 한 균종이 많고 적음보다는 균총 간의 균형이 깨진 상태를 의미하며[3], 성인이나 소아에서 여러 질환 발생에 있어 중요한 역할을 하는 것으로 알려져 있다[2-6]. 만삭아를 포함한 소아에서는 영아산통, 당뇨, 자가면역질환, 아토피 질환 등과의 연관되어 있으며, 미숙아에서는 신생아 괴사성 장염(necrotizing enterocolitis, NEC), 혹은 후기 패혈증 등과 연관되어 있다[4].

임상에서는 dysbiosis 상태를 공생 상태로 회복시키기 위해 프로바이오틱스(probiotics), 프리바이오틱스(prebiotics) 혹은 신바이오틱스(synbiotics)를 사용하는데, 적절한 양을 투여하였을 때 숙주의 건강에 유익한 효과를 나타내는 살아있는 미생물을 프로바이오틱스라고 하며[7], 프리바이오틱스는 장내 세균의 성장과 활성을 자극하는 장내에서 소화가 되지 않는 성분으로 모유 올리고당 (human milk oligosaccharide)을 포함한 여러 형태의 올리고당 혹은 락토페린 등이 이에 해당하며[7-9], 프리바이오틱스와 프로바이오틱스의 조합을 신바이오틱스라고 한다[7].

장내 미생물 집락화(gut microbial colonization) 및 관련 인자

신생아에서 미생물이 처음으로 집락화되는 시기에 대해서는 자궁 내 태아기부터 집락화가 시작된다는 가설(in utero colonization hypothesis)과 자궁 내에서는 무균의 상태를 유지하다가 출생 시 혹은 출생 직후 모체나 환경으로부터 균을 획득한다는 가설(sterile womb hypothesis) 사이에 아직은 논란의 여지가 있다[10-12]. 신생아의 장관 내에 집락화되는 세균총은 시간에 따라 서서히 변하는데, 출생 직후 건강한 만삭아의 장관은 호기성(aerobic) 환경으로 산소가 있는 곳에서도 생장할 수 있는 조건 혐기성균(facultative anaerobe)이 주를 이루며, 점차 조건 혐기성균에 의해 장내 산소 농도가 감소하면서 절대 혐기성균(obligate anaerobe)으로 균총이 변화한다[10]. 신생아 시기에는 개인 간 장내 세균총의 차이가 크지만, 영아 시기에 이유식을 시작하면서부터 장내 균종이 성인과 비슷해지다가 대개 3세경이 되면 장내 세균총이 안정화되고 개인 간의 차이는 줄어들게 된다[10,12]. 출생 후 장내 세균총의 집락화에 영향을 주는 요인에는 제태연령, 분만 방식, 식이, 항생제 사용 등이 있으며[3,4,10,12-14], 만삭아, 모유수유, 질식분만의 경우는 균종이 다양하고, 이른 시기에 집락화가 이루어지므로, 정상 세균총에 의해 생성된 단쇄 지방산(short chain fatty acid)에 의해 장관 내 pH가 낮아지면서 병원성 세균의 성장이 억제되어 공생 상태를 유지하기에 유리하다. 하지만, 그와 반대로 미숙아, 분유수유, 제왕절개 분만의 경우는 병원성 세균이 성장하기에 유리한 환경이 되어 장내 세균 불균형(gastrointestinal dysbiosis)이 쉽게 유발될 수 있다[10,12-14].

프로바이오틱스의 효과

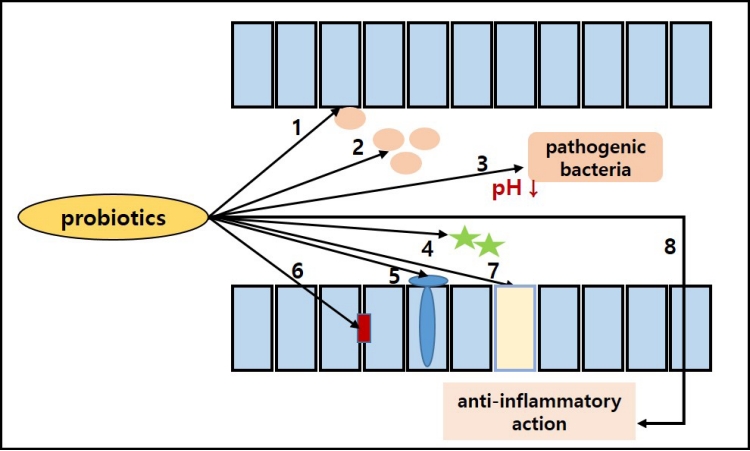

프로바이오틱스가 장내에서 효과를 나타내는 기전은 Figure 1에서 보는 것과 같이, 장내 세균(pathogenic bacteria)과 영양분을 경쟁적으로 사용할 뿐만 아니라 및 장세포에 부착될 때 필요한 수용체를 공유하고 있어 프로바이오틱스 균주에 의해 영양분과 수용체가 사용되면 이를 사용하는 장내 세균의 성장이 저해된다[7,15]. 그리고, 프로바이오틱스 내의 균주에 의해 생성된 butyrate를 포함한 여러 종류의 단쇄 지방산으로 인해 낮아진 장관 내 pH는 장내 세균의 성장을 억제시키는 효과가 있다[2,7,12]. 프로바이오틱스는 장세포의 밀착연접(tight junction) 단백질의 발현 증가를 통해 밀착연접의 기능을 강화시키거나[16], 혹은 뮤신(mucin) 분비의 증가, 장세포 분화를 통해 장의 장벽으로서의 기능(barrier function)을 강화시키는 기능을 한다[7,12,16-18]. Guo 등[19]과 Patel 등[16]의 동물 실험에서도 형광물질(fluorescein isothiocyanate–labeled dextran)과 장세포의 전기저항(transepithelial electrical resistance)을 이용하여 장의 투과성을 측정하였을 때 프로바이오틱스 사용군에서 장의 투과성과 장벽기능의 향상이 입증되었다. 그뿐만 아니라 프로바이오틱스는 여러 가지 면역반응에 관여하는데, immunoglobulin A (IgA) 나 IgG와 같은 면역 물질을 분비하거나 박테리오신, 디펜신 등과 같은 항균 물질을 분비하여 병원성 세균으로부터 장을 보호하고 장내의 염증반응을 줄이는 역할을 한다[1,7]. 프로바이오틱스는 mitogenactivated protein kinase와 nuclear factor kappa B (NF-kB) 신호전달경로(signaling pathway)의 여러 단계에도 작용하여 종양괴사인자 알파(tumor necrosis factor-α, TNF-α), NF-kB 등의 염증촉진 사이토카인(proinflammatory cytokine) 분비를 저해하는데, 병원성 세균이 Toll유사수용체(Toll like receptor, TLR)에 인식되는 단계에서부터 TNF-α 분비에 필요한 NF-kB의 핵 내 이동을 저해하여 최종적으로는 염증촉진 사이토카인인 TNF-α분비를 저해한다[20]. Lin 등[21]의 동물 실험에서도 Lactobacillus rhamnosus로 전처치한 경우 NF-kB의 분비가 억제되는 소견이 확인되었다.

The mechanism of actions of probiotics in the intestine [7]; limiting pathogenic bacterial growth (1–4), promote gut barrier function (5–7), downregulate intestinal inflammation (8). 1, competitive adherence; 2, nutrition competition; 3, production of organic acid and lowering luminal pH; 4, production of antimicrobial materials (e.g., bacteriocin, defensin, etc.); 5, increase mucin secretion; 6, increase tight junction protein production; 7, promote enterocyte differentiation; 8, anti-inflammatory action (immunoglobulin G [IgG]/IgA secretion and inhibit tumor necrosis factor-α transcription).

신생아 괴사성장염의 발병기전

미숙아는 TLR4의 활성이 증가되어있는 반면, 장의 장벽기능은 미숙한 상태로 NEC 발생의 위험이 높은 군에 해당한다. 장내 세균 불균형의 상태에서는 장내 세균총 중에서 Escherichia coli, Klebsiella, Enterobacter 등 γ-Proteobacteria가가 증가하는데[3,4,22], NEC 환자에게서는 이러한 γ-Proteobacteria의 수가 증가하고, Firmicutes 혹은 Bacteroides의 수가 감소하는 경향을 보인다. 그람음성균의 비율이 증가하는 장내 세균 불균형이 발생하면 그람음성균의 세포벽을 이루는 lipopolysaccharide가 장세포벽에 위치한 TLR4를 활성화시켜 장의 장벽기능이 손상되면서 장의 투과성 증가 및 장벽을 통한 세균전위가 일어나고, 이후 지속적이고 조절되지 않는 과장된 염증반응에 의해 장의 괴사를 특징으로 하는 NEC로 진행하게 된다[3,4,23,24].

미숙아 질환에서의 프로바이오틱스의 사용

미숙아에서 주로 사용되는 프로바이오틱스 균주들 중에서 유럽 소아소화기학회에서[25] 안정성에 대해 논의가 된 균주로는 Lactobacillus reuteri DSM17938, L. rhamnosus GG, Lactobacillus acidophilus NCDO 1748, Bifidobacterium lactis (Bifidobacterium animalis subsp. lactis) Bb-12, Bifidobacterium longum (B. longum subsp. longum), Bifidobacterium infantis (B. longum subsp. infantis) Bb-02, Bifidobacterium breve BBG-001, Streptococcus thermophilus (Streptococcus salivarius subsp. thermophilus) TH-4, Saccharomyces bouladii 등이 있으며, Bifidobacterium bifidum 중에서 이전 B. bifidum Bb-12로 명명되는 균주는 B. lactis Bb-12로, B. bifidum NCDO 1453는 B. longum으로 불리고 있다.

미숙아에서 프로바이오틱스를 투여하였을 때 효과적인 질환들을 보고한 연구들은 다음과 같다. 2020년 Sharif 등[17]이 보고한 메타 분석은 총 56개의 무작위 배정 임상시험, 10,812명의 환자를 대상으로 한 연구로, 32주 미만/1,500 g 미만 출생아(very preterm/ very low birth weight [VLBW] infant)군과 28주 미만/1,000 g 미만 출생아(extremely preterm/extremely low birth weight [ELBW] infant)군에 대해 각각 하위그룹분석(subgroup analysis)을 시행하였다. Very preterm/VLBW infant군에서는 프로바이오틱스를 사용한 군에서 18개월 이후 신경발달 예후를 호전시키지는 못하였으나, NEC, 사망, 후기 패혈증의 빈도가 유의하게 감소하였으며, extremely preterm/ELBW infant를 대상으로 한 분석에서는 NEC, 사망, 후기 패혈증 모두에 대해 두 군간 의미 있는 차이를 보이지 않았다. 무작위 배정 임상연구가 아닌 관찰연구를 대상으로 한 Olsen 등[26]의 메타분석에는 총 12개 연구에서 미숙아 10,800명이 포함되었고, Sharif 등[17]의 연구와 마찬가지로 프로바이오틱스는 NEC 발생 감소(odds ratio [OR], 0.55; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.39 to 0.78)와 사망률 감소(OR, 0.72; 95% CI, 0.61 to 0.85)에는 효과적이었나, 후기 패혈증에 대해서는 뚜렷한 효과를 보이지 않았다(OR, 0.86; 95% CI, 0.74 to 1.00). 2015년부터 현재까지 발표된 메타분석 연구 결과들을 하나의 그림으로 나타내었을 때 preterm/VLBW infant를 대상으로 한 경우는 무작위 배정 임상연구와 관찰연구 모두에서 NEC에 효과적이었으나, extremely preterm/ELBW infant를 대상으로 한 연구에서는 대다수의 연구에서 효과를 보이지 않았으며(Figure 2A), 사망에 대해서도 extremely preterm/ELBW infant를 대상으로 하였을 때는 모든 연구에서 효과를 보이지 않았다(Figure 2B).

The effect of probiotics in recent meta-analysis of randomized or non-randomized controlled trials between 2015 and 2021 for necrotizing enterocolitis (A), and mortality (B). Abbreviations: RCT, randomized controlled trial; Preterm/V, pteterm or very preterm/very low birth weight infant); E, extremely preterm/extremely low birth weight infant; RR, risk ratio; CI, confidence interval.

신생아 괴사성장염에서의 프로바이오틱스의 효과

최근 시행된 프로바이오틱스의 효과에 대한 대규모 임상연구 중 하나인 ProPrems 연구[27]는 1,099명의 미숙아를 대상으로 B. infantis, S. thermophilus, B. lactis (총 1×109 colony forming unit, CFU)를 조합하여 투여하고 후기 패혈증 발생빈도를 살펴본 연구로, 프로바이오틱스 사용군에서 후기 패혈증과 사망에는 효과를 보이지 않았지만, stage 2 이상의 NEC 발생이 감소하였다. 현재까지 보고된 개별 연구 중 가장 큰 규모의 연구인 Costelo 등[28]의 PiPS trial은 B. breve BBG-001을 사용하여 NEC stage 2 이상, 후기 패혈증, 사망에 대한 효과를 살펴보았고, 모든 결과에 대해 사용군과 비사용군 사이에 유의한 차이를 보이지 않았다. ProPrems 연구[27]와 비교하였을 때 Costelo 등[28]의 연구는 사용된 프로바이오틱스가 혼합제제가 아닌 B. breve 단독제제라는 점이 다르다.

연구들에 따라 프로바이오틱스의 NEC에 대한 효과는 다르지만, 최근 Patel 등[15]이 2016까지 발표된 총 33개의 연구를 대상으로, NEC에 대한 프로바이오틱스의 효과를 누적 분석하였을 때, 2005년 이후의 연구부터 프로바이오틱스는 신생아 NEC에 대해 지속적으로 예방효과를 보였다(OR, 0.41 to 0.49). Costelo 등[28]의 연구에서는 프로바이오틱스가 NEC에 대해 유의한 효과를 보이지 않았으나, 전체적인 누적 분석 결과에는 크게 영향을 미치지 않았다(OR, 0.53; 95% CI, 0.42 to 0.66). 최근 Razak 등[29]이 NEC에 대한 프로바이오틱스 결과의 방향을 바꾸기 위해 필요한 연구대상자 수를 시뮬레이션하였는데, 2020년 Sharif 등[17]의 코크란 연구결과를 바탕으로 하여 각각 1,800명을 대상으로 한, 다른 결과의 가상 연구들을 추가하여 누적 분석하였을 때 프로바이오틱스의 NEC에 대해 예방 효과는 변함없었으며, 약 80,000명을 대상으로 한 가상 연구 (risk ratio [RR], 1.00; 95% CI, 0.95 to 1.06)를 누적하였을 때 프로바이오틱스는 NEC에 대해 유의미한 효과를 갖지 않게 된다(RR, 1.00; 95% CI, 0.90 to 1.00). 하지만, 메타분석[17,26]에 포함된 대상자 수가 약 10,000명 정도인 것을 감안하면 대상자 수가 적은 개별 연구로는 결과를 바꾸기 위한 80,000명을 대상으로 한 가상 연구에 비해서는 부족하다.

임상적 적용: 프로바이오틱스 균주 선택

최근 프로바이오틱스에 대해 여러 가지 균주 중 가장 효과적인 균주 혹은 그 조합들을 확인하기 위해 네트워크 메타분석이 시행되고 있는데, 최근 시행된 네트워크 메타분석 중 Chi 등[30]의 연구는 프로바이오틱스 균주 간의 효과를 비교하였으며, Morgan 등[31]의 연구는 프로바이오틱스뿐만 아니라 프리바이오틱스와의 조합도 포함하여 비교하였다. Chi 등[30]의 연구에서 사망과 NEC를 예방하기 위해 연구들에서 가장 많이 사용된 균주는 Bifidobacterium 단독, Lactobacillus 단독, 그리고 Bifidobacterium/Lactobacillus 혼합제제였다. 사망에 대해서는 위약대조군과 비교하여 Bifidobacterium/Lactobacillus 조합이 Chi 등[30]의 연구(RR, 0.56; 95% CI, 0.34 to 0.84) 뿐만 아니라, Morgan 등[31]의 연구(OR, 0.56; 95% CI, 0.39 to 0.80) 둘 모두에서 효과적이었다. NEC에 대해서는, 위약 대조군과 비교하여 Bifidobacterium/prebiotics, Lactobacillus/ prebiotics, Bifidobacterium/Streptococcus, Bifidobacterium/ Lactobacillus 조합하여 사용한 경우 NEC 예방에 효과적이었다[30]. Lactobacillus/prebiotics와 Bifidobacterium/Lactobacillus의 조합을 서로 비교하였을 때는 Lactobacillus/prebiotics를 사용한 경우 Bifidobacterium/Lactobacillus와 비교하여 NEC 예방에 더욱 효과적이었다(RR, 0.13; 95% CI, 0.01 to 0.90)30). Morgan 등31)의 연구에서는 Bifidobacterium/Lactobacillus 조합(OR, 0.35; 95% CI, 0.20 to 0.59)과 B. lactis (OR, 0.31; 95% CI, 0.13 to 0.74)가 stage 2 이상의 NEC 예방에 가장 효과적이었으며, L. reuteri (OR, 0.55; 95% CI, 0.34 to 0.91)와 L. rhamnosus (OR, 0.44; 95% CI, 0.21 to 0.90)도 예방효과를 보였다. 패혈증에 대해서는 Lactobacillus/prebiotics 조합이, 완전 장관영양 도달시기와 입원기간 단축에는 Bifidobacterium/Lactobacillus 조합이 효과적이었다[30].

예후에 따라 가장 효과적인 프로바이오틱스 균주가 다른데, 사망, NEC, 패혈증, 완전 장관영양시기, 입원기간 5가지 예후를 모두를 고려하였을 때는 위약대조군에 비해 Lactobacillus/Bifidobacterium, Lactobacillus/prebiotics, Bifidobacterium/prebiotics 혼합제제가 가장 효과적이었다[30]. 그리고, Lactobacillus 단독 혹은 Bifidobacterium 단독제제로 사용한 경우는 다른 균주들과 비교하였을 때 비슷하거나 혹은 Lactobacillus/Bifidobacterium, Lactobacillus/prebiotics, Bifidobacterium/prebiotics 조합에 비해서는 좋지 못한 결과를 보였다[30].

나라별 가이드라인 및 투여 방법

프로바이오틱스 사용에 대해 각 나라에서 제시하고 있는 가이드 라인을 살펴보면, 미국 소아과학회에서는[5,32] 미국 식품의약안전처에서 승인되지 않은 상태에서 일률적인 프로바이오틱스의 사용을 추천하지 않았으며, 특히 NEC에 예방효과가 없었던 1,000 g 미만의 미숙아에서 투여하는 것은 더욱 추천하지 않았다. 캐나다 소아과학회에서는[33] 1,000 g 이상의 미숙아에서 NEC 예방을 위해 모유수유와 함께 프로바이오틱스의 사용을 고려해 볼 수 있으나, 마찬가지로 1,000 g 미만의 미숙아에서의 일률적 사용은 근거가 없다고 밝히고 있다. 유럽 소아소화기학회와[25] 미국 소화기협회에서는[34] 미숙아에서 NEC를 예방하기 위해 일부 균주에 한해 조건적으로 추천하고 있으며, 미국 소화기협회에서는 Lactobacillus와 Bifidobacterium을 조합하여 사용하도록 권고하였으며, 유럽 소아소화기학회에서는 L. rhamnosus GG ATCC53103를 사용하거나 혹은 B. infantis, B. lactis, S. thermophilus의 조합을 추천하였다. 유럽 소아소화기학회와 미국 소화기협회에서 공통적으로 추천하는 균주는 L. rhamnosus GG ATCC53103, B. infantis Bb- 02, B. lactis Bb-12였다.

프로바이오틱스 투여 방법에 대해서는 아직까지 정해진 바는 없으나, 2020년 Sharif 등[17]의 메타분석에 포함된 연구들에서는 출생 후 식이 시작과 함께 투여하고 주수나 체중에 상관없이 108–109 CFU를 하루에 1–2회로 하여 적어도 6주간(일부 연구에서는 34주에서 36주까지, 혹은 퇴원 시까지, 혹은 체중 2,000 g 될 때까지) 투여하였다. 프로바이오틱스를 투여한 후 균주가 장내에서 집락화되는데까지 걸리는 시간은 Qiao 등[35]의 연구에서는 Lactobacillus/ Bifidobacterium 혼합제제를 투여한 후 polymerase chain reaction을 통해 대변 내의 균주 수를 측정하였을 때 투여 1주 후부터 투여군과 비투여군 사이에 의미 있는 차이를 보였다. 다른 연구[28]에서는 프로바이오틱스 투여군뿐만 아니라 비투여군에서도 교차오염을 통해 균주가 장내에서 집락화되는 소견도 관찰되었다.

프로바이오틱스 투여 후 부작용 및 장기 예후

프로바이오틱스 투여 후 부작용으로는 혼합되어 있는 prebiotic oligosaccharide에 의한 복부팽만(bloating), 부글거림 (flatulence), 설사 등의 복부 불편감(intestinal discomfort)을 보일 수 있으며, 유럽 소아소화기학회에서는 L. reuteri, L. acidophilus 의 경우는 L. rhamnosus와 다르게 신경 독성이 있는 D-lactate 를 생성할 수 있으며, 미숙아에서는 아직 그 안정성이 연구되어 있지 않아 사용하지 않도록 권고하고 있다[25]. 프로바이오틱스에 포함된 균주에 의한 패혈증[1,36-38], 오염에 의한 mucormycosis [39]와 프로바이오틱스 비사용군에서의 교차오염[28]의 사례가 있으나, 빈도는 0%–0.2% [40,41]였다. 재태연령 32주 미만, 출생체중 1,500 g 미만 출생아를 대상으로 한 국내 보고에서는[42] 프로바이오틱스 투여하기 전후의 시기에 패혈증 발생빈도에는 차이가 없었으나, 프로바이오틱스와 관련된 패혈증 사례에서는 회장루를 가지고 있거나 혹은 NEC stage IIIb, 초미숙아 등과 관련되어 있음을 보고하고 있어 이러한 위험인자를 가진 환아에서는 프로바이오틱스 사용 시 패혈증 발생에 주의를 기울여야 함을 시사한다. 프로바이오틱스 사용 후 장기 예후에 있어서는 개별 연구와 메타분석 연구에서 모두 사용군과 비사용군 사이에 차이를 보이지 않았다[43,44].

결론

일부 나라에서는 특히 1,000 g 미만의 미숙아에서는 프로바이오틱스의 일률적 사용을 권하지 않고 있으나 많은 연구에서 프로바이오틱스는 NEC의 예방에 효과적이었다. 출생 체중 1,000 g 이상 출생아를 대상으로 NEC를 예방하기 위해서 프로바이오틱스를 사용하게 되는 경우는 유럽 소아소화기학회와 미국 소화기협회에서 공통적으로 추천하는 균주인 L. rhamnosus GG ATCC53103, B. infantis Bb-02, B. lactis Bb-12가 포함된 제제를 사용하고, Lactobacillus 단독 혹은 Bifidobacterium 단독으로 투여하기보다는 Lactobacillus/Bifidobacterium 혼합 혹은 Lactobacillus/ prebiotics 혹은 Bifidobacterium/prebiotics 혼합제제가 추천된다. 아직은 국내외의 식품의약품안전처의 허가를 받지 않은 상태이며, 사용 중 드물지만 프로바이오틱스와 관련된 부작용들도 보고되고 있어 사용시 주의를 요한다. 그리고, 프로바이오틱스 사용 이외에도 모유수유와 함께 장내 세균 불균형과 관련된 다른 요인들을 예방하는 노력도 함께 이루어져야하겠다.

Notes

Ethical statement

None

Conflicts of interest

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

Author contributions

Conception or design: H.W.P.

Acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data: H.W.P.

Drafting the work or revising: H.W.P.

Final approval of the manuscript: H.W.P.

Funding

None

Acknowledgements

None