|

|

- Search

| Neonatal Med > Volume 26(4); 2019 > Article |

|

Abstract

Communicating bronchopulmonary foregut malformation (CBPFM) is a communication between the respiratory and gastrointestinal tracts that can be difficult to differentiate from pulmonary sequestration or H-type tracheoesophageal fistula (TEF) because of the similarities in clinical features. A female neonate born at full term had been experiencing respiratory difficulty during feeding from the third day of life. The esophagography performed to rule out H-type TEF revealed that the esophageal bronchus directly communicated with the left lower lobe (LLL) of the lung. Lobectomy of the LLL, fistulectomy of the esophagobronchial fistula, and primary repair of the esophagus were performed. Finally, CBPFM type III with pulmonary sequestration was confirmed on the basis of the postoperative histopathological finding. We report the first newborn case of CBPFM type III with pulmonary sequestration in Korea.

Communicating bronchopulmonary foregut malformation (CBPFM) is a rare congenital anomaly of the communication between the respiratory and gastrointestinal (GI) tracts. Depending on whether the respiratory tract connected to the GI tract is a main or lobar bronchus, CBPFM can be classified as esophageal lung or esophageal bronchus [1-3]. The clinical presentations of CBPFM are similar to that of H-type tracheoesophageal fistula (TEF) and can be difficult to differentiate from those of pulmonary sequestration [4,5]. In Korea, only five cases have been reported in the literature, of which one was diagnosed in the newborn period as CBPFM-type IA [5-9]. We describe the first reported case of newborn CBPFM type III with pulmonary sequestration diagnosed in Korea.

The patient was a female neonate born at 40 weeks of gestation with a birth weight of 3.58 kg. The mother was a 39-year-old primigravida woman. At the gestational age of 20 weeks, gastric gas was absent but polyhydramnios was observed on fetal ultrasonography suggesting TEF.

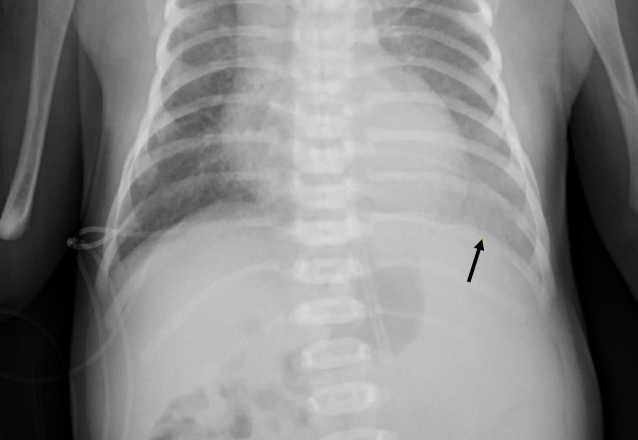

The patient had Apgar scores of 9 and 10 at 1 and 5 minutes after vaginal delivery, respectively. After giving birth, her arterial oxygen saturation level was within the normal range at 95% to 100%. The nasogastric tube inserted in the esophagus to rule out TEF was positioned on the stomach smoothly. Despite mild haziness in the left lower lobe (LLL) on chest radiography (Figure 1), she showed no sign of respiratory difficulty. Thereafter, the nasogastric tube was removed, and oral feeding was started.

Although she did not show any sign of respiratory difficulty, her oxygen saturation level occasionally decreased to <90% and promptly recovered with 0.1 L/min oxygen supplementation via a nasal cannula. The echocardiography performed on day 1 revealed patent ductus arteriosus (PDA) and a muscular trabecular ventricular septal defect (VSD) with a bidirectional shunt.

During the first 3 days after birth, she exhibited tachypnea and tachycardia, with chest retraction only during oral feeding. Physical examination revealed a few crackles in the LLL field. Chest radiography revealed an area of haziness in the LLL field. An infection workup revealed a C-reactive protein level of 11.43 mg/mL (reference range, 0 to 0.3) and white blood cell count of 11,540/μL (reference range, 3,150 to 8,630), consisting of 71.2% segmented neutrophils and 19.4% lymphocytes. Under the impression of aspiration pneumonia, enteral feeding was stopped and intravenous administration of antibiotics (ampicillin and cefotaxime) was initiated. However, no microorganism was detected on the culture surveillance.

Owing to her feeding-associated respiratory symptom and chest radiography findings that suggested aspiration pneumonia, esophagography was performed 5 days after birth to rule out H-type TEF. The esophagogram showed the esophageal bronchus directly communicating with the LLL of the lung with right gastric diverticulum and intestinal malrotation. At 7 days of age, computed tomography (CT) of the thorax confirmed the CBPFM in the LLL, which was supplied by at least 3 arteries, including the celiac axis, upper abdominal aorta, and lower descending thoracic aorta, draining into the pulmonary vein (Figure 2).

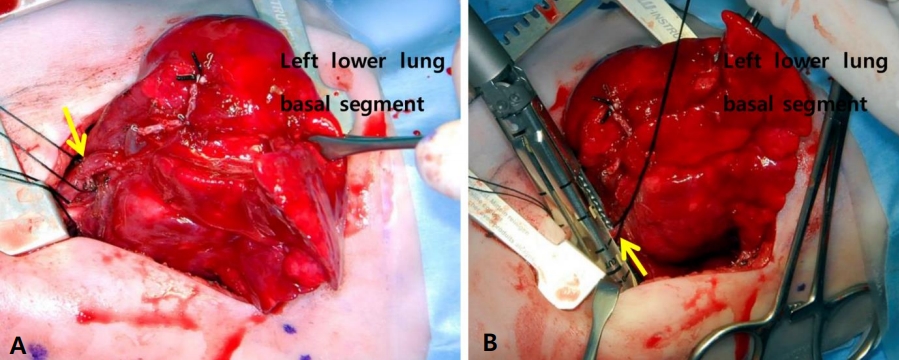

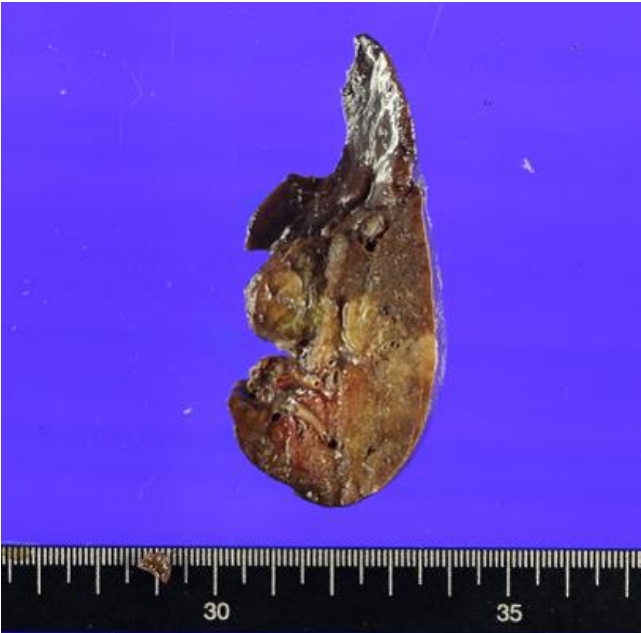

Surgical treatment of the lesion was performed at 21 days of age, and the lesion weighed 3.95 kg at that time. Exploration via posterolateral thoracotomy revealed the collapsed, non-aerated LLL. During the surgery, the fistula was found to be attached to the lower thoracic esophagus, which communicated with the bronchus connecting to the basal segments of the LLL. Unlike the CT scan results, the real blood supply to the basal segments of the LLL was found to come from the descending thoracic aorta during the operation. The superior segment of the LLL was supplied by the pulmonary artery. The diagnosis was esophageal bronchus with pulmonary sequestration. Lobectomy of the LLL, fistulectomy of the esophagobronchial fistula, and primary repair of the esophagus were performed (Figures 3, 4). The fistula seemed to have bronchus tissue of 0.8×0.6 cm in size that was divided close to the esophagus and then primarily closed with 3–0 black silk suture. Histopathological examination of the fistula revealed a peribronchial dense fibrosis and pseudoangiomatous change in the fistula tract, a finding similar to that in the bronchiole but without any finding of esophageal origin.

Enteral feeding was initiated on postoperative day 7. One month later, she received Ladd’s operation for the intestinal malrotation. After the surgery, she was well and tolerated complete oral feeding. PDA and muscular VSD were closed on the follow-up echocardiography at 14 days after birth. At 2 months and 10 days after birth, she was discharged without a nasogastric tube and weighted 5.1 kg at that time. At 13 months after the surgery, she was doing well without any complications such as recurrent aspiration during bottle feeding, esophageal stenosis, or respiratory tract infection.

In our case, a female newborn initially suspected as having a C-type TEF in the prenatal period or H-type TEF after birth was finally diagnosed as having CBPFM type III with pulmonary sequestration on the basis of the postoperative histopathological finding.

CBPFM type III, in which the segmental bronchus arises from the esophagus, is a rare congenital anomaly. The incidence in the neonatal period is rare, and neonatal patients are diagnosed incidentally while being investigated for some other associated anomaly [2,10]. Clinical presentations are recurrent aspiration episodes or respiratory tract infection in most cases; thus, these are often diagnosed at the age of ≥1 month after birth [3,5,7,10,11]. To date, only four cases of CBPFM type III, including the present case, have been diagnosed within the first week of life [3,10,12-14].

CBPFM can be called “esophageal lung” or “esophageal bronchus” depending on whether a main or lobar bronchus is attached to the foregut (esophagus or stomach). Thus, in our case, CBPFM type III can also be called esophageal bronchus because the fistula involved the bronchus connecting to the basal segments of the LLL. CBPFM is the result of a focal mesodermal defect in the part of the lung bud on the esophagus, which is related to the budding defects, and differentiation or separation of the primitive foregut [1,15,16].

In 1968, Gerle et al. [17] first proposed the diagnosis of CBPFM, and Srikanth et al. [16] established a classification system for CBPFM. According to the CBPFM classification system proposed by Srikanth et al. [16], the present case can be classified as CBPFM type III, defined as an isolated anatomic lobe or a segment communicating with the esophagus (Table 1) [11,16]. Especially types III and IV differ in histological findings. In type IV, the communicating channel may have continuity with the bronchopulmonary tract and esophagus. This characteristic is confirmed by the histopathological findings of the aberrant tissue in the bronchopulmonary tract and esophagus [16]. However, in our case, the histopathological finding of the fistula showed only a bronchiole origin, which suggested CBPFM type III.

Only approximately 70 CBPFM cases have been reported in the literature worldwide. Unless other anomalies are combined, CBPFM is rarely diagnosed in the newborn period because most cases are diagnosed owing to repeated respiratory infections [10]. Excluding our case, four of five cases in Korea were diagnosed at least 5 months after birth [5-7,9]. One case in Korea was diagnosed as CBPFM type IA on the day of birth and had another associated anomaly, esophageal atresia with C-type TEF [5]. In that case, the diagnosis could be made earlier because of the early onset of symptoms, including failure of gavage tube insertion [5]. However, in our case, the diagnosis was more difficult because of the absence of esophageal atresia. However, we considered the possibility of H-type TEF on the basis of the prenatal ultrasonographic findings. H-type TEF and CBPFM type III have similar clinical manifestations, including choking, coughing, or cyanosis during feeding [18]. However, the two types have structural differences. H-type TEF is a rare type of fistula that results from abnormal communication between the esophagus and the trachea, a nonbronchopulmonary system [18]. However, in CBPFM type III, the trachea has a normal structure, but the bronchus below the level of the trachea has a fistula connected to the esophagus.

The main difference between esophageal bronchus and pulmonary sequestration is the blood supply [2]; the blood supply of the esophageal bronchus comes from the pulmonary artery, whereas that of pulmonary sequestration is from the systemic circulation [2]. In our case, the superior segment of the LLL was supplied by the pulmonary artery, and the basal segment was supplied by the descending thoracic aorta. The final diagnosis, therefore, was CBPFM type III with pulmonary sequestration [16,19]. Patients with CBPFM are often associated with congenital anomalies, including foregut diverticulae, duplication cyst, TEF, and cardiac anomalies [4]. Especially TEF and cardiac anomalies, such as PDA and dextrocardia, are more commonly associated anomalies in most cases [5,8]. This patient had a right gastric diverticulum, which is a type of foregut diverticulae, and cardiac anomalies (PDA and VSD).

Treatment is usually pneumonectomy of the affected segment or lung lesion with esophageal repair [4,5]. Bronchial reimplantation is also considered in patients with normal vasculature [5]. However, the results could be unsatisfactory because of the mortality and morbidity caused by complications such as bronchial anastomosis site stenosis [5]. The long-term prognosis of CBPFM is usually favorable if diagnosed early and accurately, and if procedures such as pneumonectomy are performed immediately [5].

CBPFM type III, a rare congenital anomaly, is difficult to differentiate from H-type TEF or pulmonary sequestration, and usually diagnosed after birth unless associated anomalies, including esophageal atresia, exist. CBPFM should be included in the differential diagnosis, along with H-type TEF, when feeding-associated respiratory difficulty or frequent aspiration pneumonia-like event is observed in a newborn. We report the first reported Korean case of esophageal bronchus diagnosed early in the newborn period using CT and barium esophagography.

ARTICLE INFORMATION

Figure 1.

Chest radiograph after gastric tube insertion (at birth). Increased opacity is found involving the left lower lung field (solid arrow). The cardiac size is borderline. A feeding tube is placed with its tip on the stomach, which is located more medial than usual and associated with visible small bowel gases in the right abdomen, suspected to be gastrointestinal malrotation.

Figure 2.

(A) Esophagogram. The esophagus is directly communicating with the bronchus from the left lower lobe of the lung (solid arrow), combined with a suspected right gastric diverticulum (dotted arrow). (B) Chest computed tomography scans (coronal view). The left lower lobe, which contains atelectasis and consolidation, is supplied by the aberrant artery arising from the celiac trunk. A lesion suspected to be a fistula (solid arrow) is found between the esophagus and the bronchus.

Figure 3.

(A) Intraoperative demonstration of the anatomy. The feeding artery (solid arrow) from the celiac trunk is depicted. (B) Intraoperative demonstration of the anatomy. The fistula (solid arrow) connecting the esophagus to the bronchus is shown.

Figure 4.

Gross surgical specimen of the resected left lower lobe. The left lower lobe tissue measures 8×5×3 cm. The gross finding shows bronchiectasis or a dilatated cystic area.

Table 1.

Classification System of Communicating Bronchopulmonary Foregut Malformation [16]

REFERENCES

1. Bokka S, Jaiswal AA, Behera BK, Mohanty MK, Khare MK, Garg AK. Esophageal lung: a rare type of communicating bronchopulmonary foregut malformation, case report with review of literature. J Indian Assoc Pediatr Surg 2015;20:92–4.

2. Sugandhi N, Sharma P, Agarwala S, Kabra SK, Gupta AK, Gupta DK. Esophageal lung: presentation, management, and review of literature. J Pediatr Surg 2011;46:1634–7.

3. Verma A, Mohan S, Kathuria M, Baijal SS. Esophageal bronchus: case report and review of the literature. Acta Radiol 2008;49:138–41.

4. Pimpalwar AP, Hassan SF. Esophageal bronchus in an infant: a rare cause of recurrent pneumonia. J Pediatr Surg 2012;47:e5. –8.

5. Chung JH, Lim GY, Kim SY. Esophageal lung diagnosed following the primary repair of esophageal atresia with tracheo-esophageal fistula in a neonate. Surg Radiol Anat 2014;36:397–400.

6. Kim CW, Kim DH. Single-incision video-assisted thoracic surgery lobectomy in the treatment of adult communicating bronchopulmonary foregut malformation with large aberrant artery. J Thorac Dis 2016;8:E148–51.

7. Park T, Jung K, Kim HY, Jung SE, Park KW. Thoracoscopic management of a communicating bronchopulmonary foregut malformation in a 23-month-old child. J Pediatr Surg 2012;47:e21. –3.

8. Eom DW, Kang GH, Kim JW, Ryu DS. Unusual bronchopulmonary foregut malformation associated with pericardial defect: bronchogenic cyst communicating with tubular esophageal duplication. J Korean Med Sci 2007;22:564–7.

9. Kim CY, Goo HW, Kim HJ, Choi SJ, Cho YS, Lee JH, et al. Communicating bronchopulmonary foregut malformation: a case report. J Korean Radiol Soc 2000;43:59–61.

10. Rathi V, Deshpande S, Nazim A, Domkundwar S. Esophageal lung: a rare case of communicating bronchopulmonary foregut malformation. Indian J Basic Appl Med Res 2017;6:450–4.

11. Ren H, Duan L, Zhao B, Wu X, Zhang H, Liu C. Diagnosis and treatment of communicating bronchopulmonary foregut malformation: report of two cases and review of the literature. Medicine (Baltimore) 2017;96:e6307.

12. Lacina S, Townley R, Radecki L, Stockinger F, Wyngaarden M. Esophageal lung with cardiac abnormalities. Chest 1981;79:468–70.

13. Heithoff KB, Sane SM, Williams HJ, Jarvis CJ, Carter J, Kane P, et al. Bronchopulmonary foregut malformations: a unifying etiological concept. AJR Am J Roentgenol 1976;126:46–55.

14. Hanna EA. Broncho-esophageal fistula with total sequestration of the right lung. Ann Surg 1964;159:599–603.

15. Leithiser RE Jr, Capitanio MA, Macpherson RI, Wood BP. "Communicating" bronchopulmonary foregut malformations. AJR Am J Roentgenol 1986;146:227–31.

16. Srikanth MS, Ford EG, Stanley P, Mahour GH. Communicating bronchopulmonary foregut malformations: classification and embryogenesis. J Pediatr Surg 1992;27:732–6.

17. Gerle RD, Jaretzki A 3rd, Ashley CA, Berne AS. Congenital bronchopulmonary-foregut malformation: pulmonary sequestration communicating with the gastrointestinal tract. N Engl J Med 1968;278:1413–9.

18. Elumalai G, Arjet H. “Tracheoesophageal fistula” embryological basis and its clinical significance. Int J Dev Biol 2016;100:43414–9.